There are 23 government-operated warming centers — a short-term emergency shelter location open during extreme low temperatures — in the greater Cincinnati area.

There are nine in Columbus.

There are four in Cleveland.

But the sole warming center in Licking County — where more than 200 people are homeless on any given night, according to a recent census conducted by the Department of Housing and Urban Development — is run entirely by volunteers from a coalition of local nonprofits, churches and emergency response agencies.

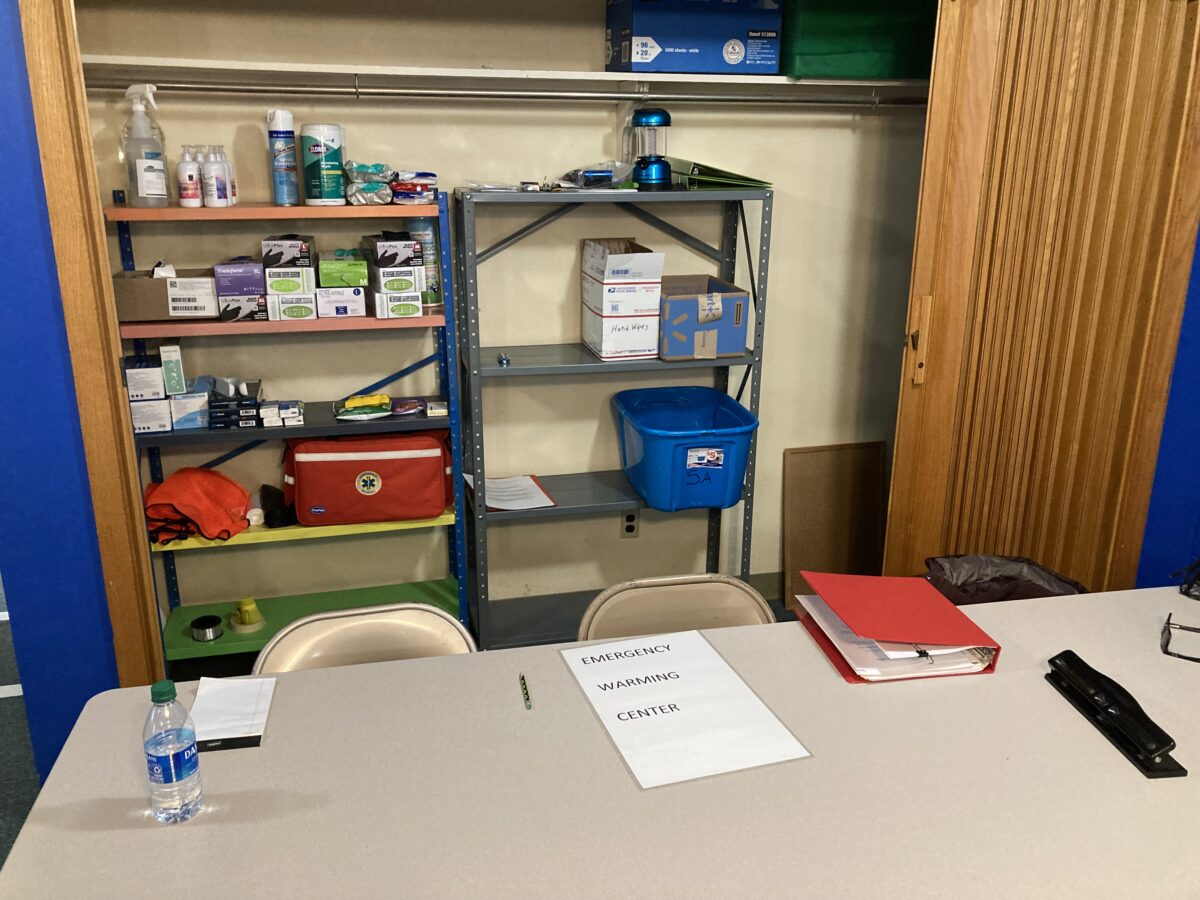

And the center, run out of a repurposed church basement and framed by cloth drapes and garbage bag-covered windows to block streetlights, has been open just six days in 2024.

In Licking County, 13 in every 10,000 residents are unsheltered. That’s significantly higher than counties with similar populations like Medina County, where just two people per 10,000 residents are unsheltered.

When temperatures drop below freezing, the private citizens who provide support struggle to meet the constant, growing need.

Developing a warming center

Until 2019, there were zero warming shelters in Licking County, but when subzero temperatures, snow emergencies and Winter Storm Jayden came through in late January, there was no time for delay.

On Jan. 29 that year, Jeff Gill, then pastor of Newark’s Central Christian Church, got some troubling news from a colleague in charge of developing a pop-up warming center: they hadn’t planned ahead.

“He said … ‘I guess we’ll have to work on that for next year,’” Gill remembered. Then, “I said some stuff a preacher shouldn’t say in his church office.”

After that conversation, he sent two emails: one to the chair of the board, and another to the chair of trustees at Central Christian.

“God bless them. Both of them got back to me within 5- 6 minutes and said: ‘I’m at work but I support you. What do you think we should do?’” Gill said.

The Licking County Emergency Warming Center was opened at Newark’s Central Christian Church that year, alongside another at the now-closed Disciple Factory.

The location changed the next year to Holy Trinity Lutheran Church in Newark.

“Our community was looking at the homeless situation and getting ready to do some attempts to address chronic homelessness in the county, which led to a homelessness task force,” said Deb Dingus, the pastor at Holy Trinity.

The following year, Dingus began conversations to get other entities involved. From there, more task force members joined the coalition, as did the Licking County Emergency Management Agency and the Red Cross.

“Once the task force was put into existence, LMH [Licking Memorial Hospital] has provided the food,” said Patricia Perry, task force member and head of Newark Homeless Outreach, an organization that provides resources to unhoused people every Saturday.

On top of food, Licking Memorial Hospital has provided transportation, bringing people who are unsheltered to Holy Trinity.

More than a warming center

Beyond food and transport, volunteers at the warming center at Holy Trinity provide kindness.

Task force member Linda Mossholder has seen how small gestures can warm people’s hearts. She goes out of her way to remember the little things about people, and the guests at the warming center are pleasantly surprised when she brings them their coffee orders, memorized.

“[One guest] said, ‘you know, nobody has ever asked me even what I want in my coffee, let alone remember what I take in it,’” Mossholder said. “And he says, ‘That means a lot to me.’”

Perry has witnessed similar joy when bringing tobacco and rolling papers to guests at the warming center.

“It’s just about going outside and having a cup of coffee and a cigarette,” Perry said. “They [people utilizing the shelter] are used to having to look over their shoulders, but in that warming center, it’s 100% a safe space.”

To increase accessibility, the warming center has no barriers to entry, meaning those with pets and those using substances are welcome — atypical for shelters in Licking County.

“We’re saving people from freezing to death,” said Nancy Welu, the volunteer coordinator of the Licking County Emergency Warming Center Task Force and the academic administrative assistant for Denison University’s anthropology department.

“You’re going to be warm,” she said. “You’re going to be treated with respect. You’re going to have a full belly.”

While their services spread love and care, the reality volunteers and guests at the warming center face reflect a society that does not do the same.

“You have folks that are working full-time jobs, and they’re coming to the warming shelter because it’s too cold to sleep in their car,” Dingus said. “The best thing to do is get to know people and get to know their particular stories and start helping people where they’re at.”

Dingus lives by these words, going above and beyond to get to know her community members and their needs, no matter their situation.

Growing population, growing need

While interactions at the warming center are soul-stirring, the need for it is indicative of a growing oversight.

According to HUD, about 10,654 people were unhoused on a given night in Ohio in 2022, or around nine per 10,000 people in the state. At least 215 of those people were homeless in Licking County, according to the Licking County Coalition for Housing.

In 2024, though, that population has grown to 237 people — a more than 10% increase in just two years.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service, hypothermia deaths can occur in temperatures as warm as 40 degrees Fahrenheit. If the temperature remains in the 40-degree range or below, unhoused and unsheltered people are in danger.

Even so, Newark’s warming center is unable to open until the temperature falls below 10 degrees Fahrenheit.

“We want it to be consistent,” said Red Cross Senior Disaster Program Manager and task force member Tim Callahan. “[If] it’s 10 degrees this week, [and if] next week it’s 15 degrees, then people get confused.”

Volunteer availability also complicates the warming center’s ability to open at higher temperatures.

“I know folks in the community would like us to activate sooner than that, but for every five degrees, you’re going to be open more, which then takes more volunteers,” Welu said.

Finding volunteers is difficult, and the center’s attendance is growing.

“Last year, we were averaging 37 [people looking for shelter per night],” Dingus said. “This last time that we were open we were somewhere between 39 to 43.”

That may not sound like a drastic increase, but as these numbers rise, so does the need for volunteers to manage the many resources required to run the center. Welu is well aware of this difficulty.

“Last year when we were open for three days at Christmas I took it upon myself to wash all the blankets,” Welu said. “I just paid out of pocket to have them all cleaned… about 150 bucks to get a couple hundred.”

This year, with the help of task force member and Pathways of Central Ohio member Kristin McCloud , the group obtained $360 worth of gift cards to cover the cost of washing the blankets.

Long-term solutions, not Band-Aids

After a 50-day walk around Licking County in 2016, Dingus said she knew the region needed a low-barrier shelter.

“I was seeing and actually sleeping outside for 50 nights,” Dingus said. “I was hearing and learning from people who were experiencing homelessness.”

The need, she said, is to create a shelter without sobriety or income requirements. Those low-barrier shelters exist without policies that “make it difficult to enter the shelter, stay in the shelter, or access housing and income opportunities,” according to National Alliance to End Homelessness.

But Perry said that’s still out of reach, in part because local leadership doesn’t have the funds — or the motivation — to create the low-barrier shelter.

And public officials, including Newark Mayor Jeff Hall and County Commissioner Tim Bubb, said a low-barrier shelter isn’t in the cards.

“The money almost has to come through a levy or something county-wide and there hasn’t been a desire,” said Newark Mayor Jeff Hall.

Commissioner Bubb agreed.

“At the moment, I’m not aware of any efforts in the county to do a low-barrier shelter,” said Bubb.

While county officials may not have their boots on the ground every day like Perry, Bubb and co-commissioner Duane Flowers said they’re working to provide aid, funding and support.

“Not just money, but also materials and also support,” Bubb said. “We coordinated with the churches that have done that over the past several years to provide cots and support for the warming centers as needed.”

Advocates like Perry and Deborah Tegtmeyer, the executive director of LCCH, believe that without a city or county buy-in, there is no realistic way to get a year-round low-barrier shelter off the ground in Licking County.

“I don’t know if it’s going to happen in the next 10 years. I really don’t,” Tegtmeyer said. “We could certainly use one with the infusion of money coming to this community,” said Tegtmeyer.

With temperatures dropping below freezing this mid-March week, the warming center task force remains vigilant.

“We’re doing the best we can do without more volunteers,” Perry said. “If anybody wants to volunteer, reach out to Nancy Welu!”

This story was updated Sunday, March 24 at 12:50 p.m. to correct the name of Kristin McCloud. The Reporting Project regrets the error.

Noah Fishman writes for TheReportingProject.org, the nonprofit news organization of Denison University’s Journalism program, which is sponsored in part by the Mellon Foundation and donations from readers. Sign up for The Reporting Project newsletter here.