As Valerie Mockus set off for college in August of 1990 from her rural Ohio village, where her family roots run five generations deep, she didn’t think for a minute that she would return.

She had dreams to chase, and like a lot of teens who grow up in small towns and rural areas, the future was far from Hebron, population 2,355.

Or so it seemed. Time and distance can change a person’s mind, and after a couple of decades away, she felt a calling to head back to rural Ohio.

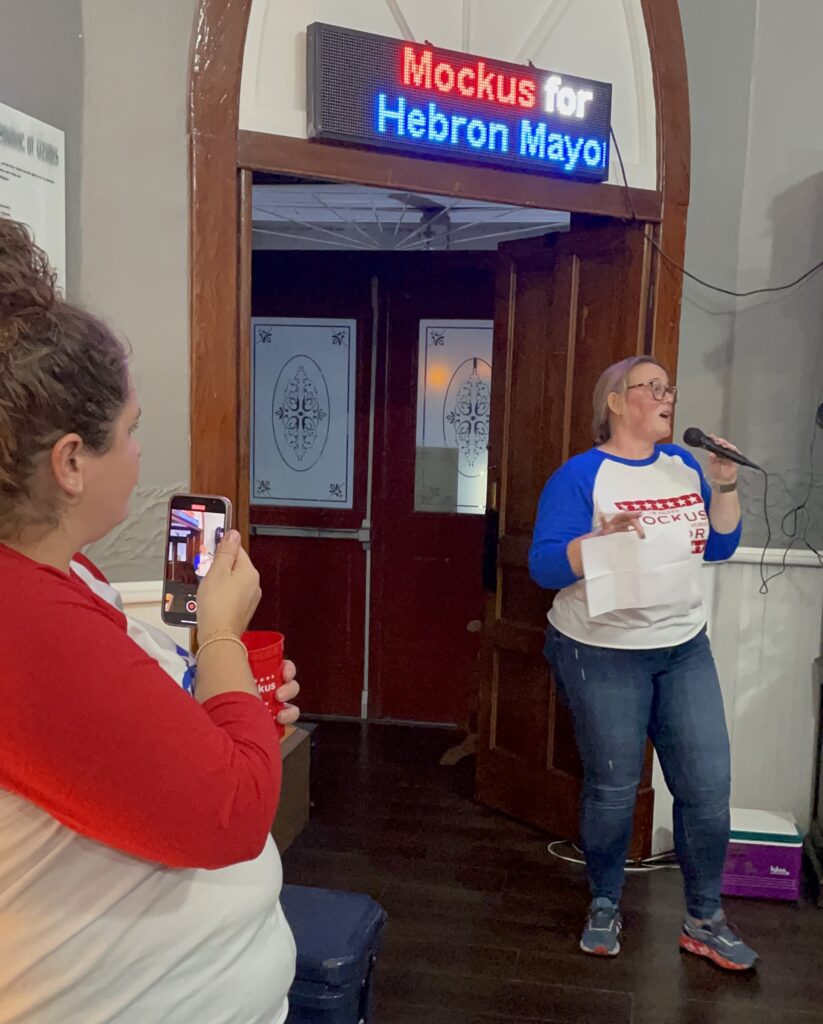

It was so strong that when Mockus returned to Hebron, she was deeply in love with the place she called home – so much so that she ran for mayor. The rookie was unsuccessful on her first try, but she secured a seat on the village council, and in November, she was elected mayor of Hebron.

The village is located on Rt. 40, the old National Road, near the intersection of I-70 and Rt. 79. It’s just south of Newark and Heath, and 30 miles east of Columbus, and it has plenty of water, making it attractive to industry. Microsoft, for example, recently announced interest in 200 acres there for data centers.

Mockus, 51, the first woman mayor of Hebron, founded in 1827, was sworn into office on New Years Day by Annelle Porter, who became the first woman on the village council in the 1970s.

“When I first left home for school, I never thought I would end up back in Hebron, much less become the mayor,” said Mockus, president of Apple Pi Consulting, which she and her husband, Gary, operate from their home. After graduating from Lakewood High School, and then Denison University, Valerie Mockus spent 25 years living in cities across the Midwest and eastern seaboard for her work as a financial aid consultant for colleges and her pursuit of a master’s degree and doctorate.

She is not alone in leaving her rural hometown, but unlike her, many never return.

“Brain drain is the biggest problem facing rural America,” said Will Drabold, a vice president at Sunday Creek Horizons, a consulting firm in Athens, Ohio, that serves Appalachian and other rural communities. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, “in 2019, the year before the pandemic hit the United States, smaller counties with fewer than 30,000 people lost population through net domestic migration.”

However, like everything else, the COVID-19 pandemic changed everything.

“During the pandemic’s peak, between 2020 and 2021 … [the] least populous counties gained people through domestic migration,” according to a report by the Census Bureau. But these gains were short-lived. That same census report found that “on average, small counties that saw growth in net domestic migration the first year of the pandemic returned to pre-pandemic levels of slow or declining net domestic migration from 2021 to 2022.”

According to Sarah Melotte of The Daily Yonder, rural counties reported a slight population growth of 0.13%, challenging the previous trend of decline.

Data from the Economic Innovation Group show that remote work opportunities significantly influence population growth and migration patterns across the United States and that working from home is a significant factor in the uptick in migration back to rural areas.

For many rural areas, brain drain has become such a significant issue that programs to address it have gained governmental support. In West Virginia, Ascend WV offers people financial incentives to move into rural West Virginia and work remotely. It will give young and talented remote workers “$10,000, paid in monthly installments” and an additional $2,000 once they complete their “second consecutive year” in the program.

In Ohio, the City of Hamilton, north of Cincinnati, offers recent college graduates up to $15,000 toward student-loan repayment if they move to the city.

As enticing as such programs might be for some people, others return home for family and other reasons. Mockus is among them.

“I didn’t want to be in a place with friction,” she said. “I wanted to be close to the community and the roots of my family that exist here.”

Once Mockus decided to return home to Hebron, she went all in. She and her husband bought her childhood church at auction for $80,000 and committed to restoring and transforming it into a beautiful home. She delved into local politics, which led her to a seat on the village council and, ultimately, launched her second mayoral campaign.

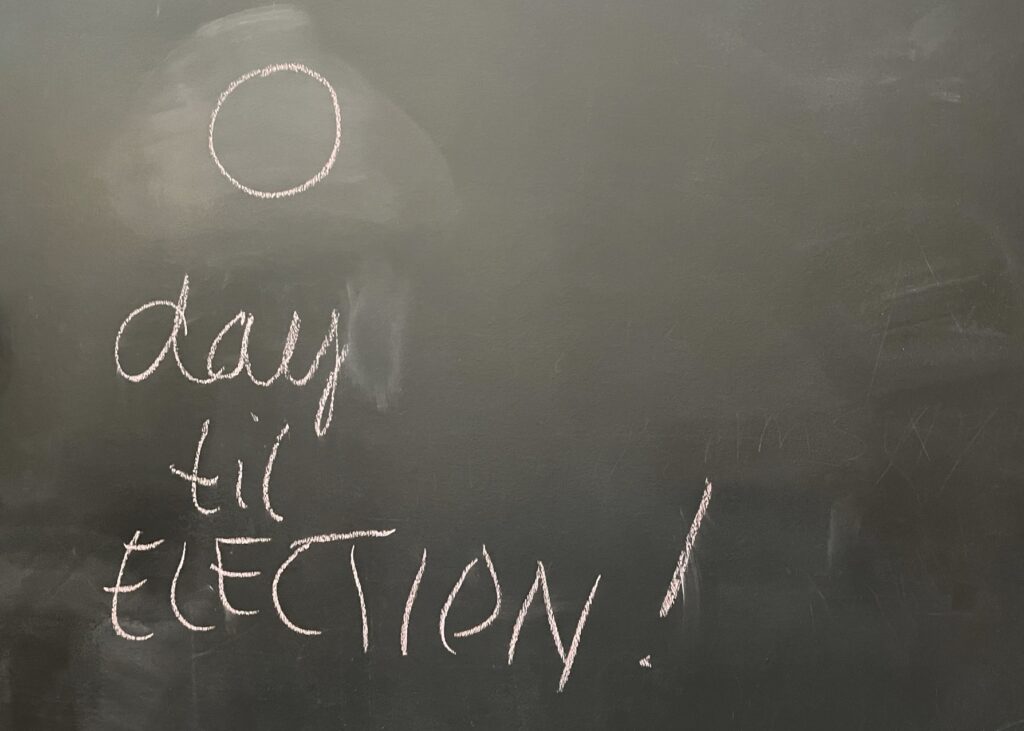

On election night in November, “The Chouse,” as Mockus affectionately calls their church-house, was full of nervous energy. The sanctuary that once was lined with pews sat full of people on couches and in comfortable chairs waiting to celebrate a new mayor. Mockus’s husband distracted himself by serving guests at “The Confessional,” a handmade bar at one end of their living room.

When the volunteer runner who went to gather election results from the village polling center doors returned and announced Mockus’s victory, the room erupted in cheers.

Everyone except Mockus.

She and a few of her closest friends and supporters gathered in her expansive kitchen for a private moment of celebration and a group hug. The women huddled together and let their emotions go. Tears, smiles and thank-yous flowed.

The journey to this point was long for Mockus, and it wasn’t always a clear path.

Being a fifth generation Hebronite, leaving town to go to college – even as close as Denison University in Granville, eight miles away – was a major step for her.

Although she was still so close to home, she felt disconnected from her town and her support system in Hebron.

“I lost my way in the first few years of college,” Mockus said. “It wasn’t until around the end of my sophomore year, when I changed majors, that I finally felt like I had found my footing and place on campus.”

She established herself on campus and graduated as the first Women and Gender Studies major in Denison’s history.

After her undergraduate studies, Mockus moved around the country to be near the colleges and universities where she worked.

“I basically followed work; I migrated for work,” Mockus said. From Wooster to Gambier and later New York and Key West, Mockus worked for colleges while also earning higher degrees and building up her consulting business with her husband.

While living in Key West, the couple decided to move back to Ohio.

“I realized there was no way I could live in Party Town, USA, and try to be successful in a doctoral program,” Mockus said.

Then, while looking for a house in a walkable community back in Ohio, she stumbled upon her childhood church, which had closed and was up for sale. After a quick walk-through, and persuading her husband that the classic white church with a steeple could be their home, they won it at auction and began renovation work.

“This is where I grew up, and these are my people,” Mockus said.

Her single mom worked a second-shift job, so she was raised by her grandma and mom.

“This [town] was my grandma’s anchor, like my grandma was for me,” Mockus said. “When I think about my grandma, I think about this village … and that makes me feel comfortable in this town.”

Still, she saw ways the village could improve, and she was inspired to help.

“I was open when people talked to me about their ideas,” Mockus said. “Being out there and talking to people and serving people is what I wanted to do.”

Instead of trying to tell people how to do things, she took her experiences from her consulting work and used them to work with people to help build the village of their hopes and dreams. This approach helped ingratiate her to voters, leading her to win the election.

“She’ll be a good steward for the town,” said James Layton, the former mayor who did not seek another term. “She’ll do what’s best for the village. She embodies the Hebron way and can make things happen the right way.”

Even some people who live near Hebron but not in the village supported Mockus.

“Her grandma raised her right,” said Jack Justice, who lives just outside of the village limits. “I’ve known her since she was small, and she’s earned a lot of respect from the locals in the time she’s been back in town.”

Mockus was known as a giver well before her mayoral runs.

“The people [here] are good, and she wants to give back,” said Gary Mockus, Valerie’s husband and business partner. “There is something in her that makes her want to help those who brought her up.”

To many in Hebron, Valerie Mockus embodies the promise of what the village can be as central Ohio grows. Mockus hopes that while serving her community she also can serve as an example for those who want to move to small towns across the country.

Josh Thomas writes for TheReportingProject.org, the nonprofit news organization of Denison University’s Journalism program, which is sponsored in part by the Mellon Foundation and donations from readers. Sign up for The Reporting Project newsletter here.