Confronting the difficult truths of a changing Southern landscape.

By Lyndsey Gilpin

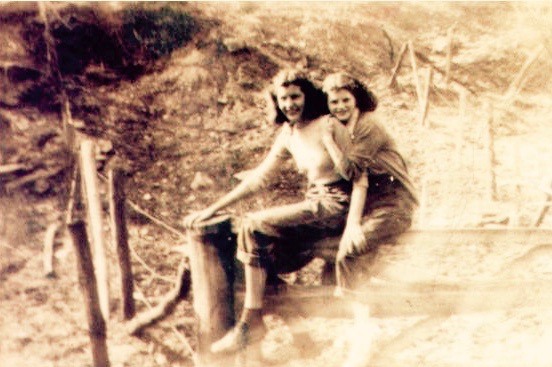

In the faded photo, my grandmother is 14 years old, huddled close to her best friend on a wooden fence somewhere in Eastern Kentucky. She’s wearing a sweater and rolled-up jeans, the humidity frizzing her chestnut-brown hair. The Appalachian mountainside climbs straight up behind them, leaves and snapped branches littering the ground. Her smile is so wide, my mom always says, she can hear the laughter.

It’s one of the few photos my family has of the childhood she spent in Greasy Creek, a sleepy unincorporated community and former coal town in Pike County. Two years later, her parents kicked her out of the house for being pregnant; 35 years and five children after that, she died of abdominal cancer. I never met her. For as long as I can remember, I’ve searched for answers about my grandmother and the place she grew up, the place that my maternal blood is from, a place I feel close to in my bones but don’t understand. I’ve stared at the photo, studying the trees and the dirt. I’ve questioned family members. I’ve scrambled around hillside cemeteries with my mom, searching for her kin. I once consulted a spiritualist medium at a place called the “Intuitive Connection,” just in case.

To uncover the truth about the place she was from, the life she might have lived, how those mountains might have shaped her, I became a journalist. The first essay I ever wrote, at age 11, was a memoir about her; when it was published in the local newspaper and I saw my byline, I chose this path and never looked back. I went to graduate school, traveled around the U.S., landed a fellowship at an esteemed magazine in Colorado, led an influential investigation.

I watched from afar as other writers parachuted in to my family’s homeland to tell the stories of Southern people and places. They showed up for the natural disasters: Hurricane Matthew in North Carolina, the 2016 wildfire in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. They showed up for the industrial ones: the 2008 coal ash spill in Roane County, Tennessee, which was the largest in history, or the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. They bloviated about the dying coal industry while ignoring the people whose lives depended on it and whose livelihoods were harmed by it.

Meanwhile, the people in political and economic power insisted coal was the only hope for Appalachia, that climate change wasn’t real and those who call the disappearing Gulf Coast home have nothing to fear. They continue to exploit communities of color and low-income communities by luring prisons, pipelines, and chemical plants to open here, touting local jobs that usually never materialize, at least to the extent promised. All levels of government have failed to invest in sustainable local economies that empowered workers and marginalized groups, which has resulted in extractive industries that have contaminated land, caused public health crises, and pigeon-holed rural areas.

The South’s racial, environmental, and political history is violent and severely unjust.The wounds have never never fully healed; they are ripped open each day with stories highlighting poverty and backwardness at the expense of context and complexity. As a result, complicated issues like climate change, economic development, natural resources, and class and race relations are boiled down to a jarring sound bite that reverberates around the internet, perpetuating stereotypes and reinforcing the idea that Southerners aren’t willing to reckon with the past and move forward. It all contributes to a sense of fatalism that is palpable in many rural communities.

Donald Trump won every Southern state except Virginia in the 2016 presidential election by a significant margin. Contrary to popular belief, statistics revealed that affluent white voters, not simply the rural working class, tipped the vote. But as usual, this region’s rural areas shouldered the country’s blame, even though its systemic problems persist everywhere: north or south, rural or urban, wealthy or poor.

A few weeks after the election, I looked out the window of my home in Colorado at the two jagged, snow-covered peaks in the distance. My bones ached for the rolling green mountains of Appalachia, for hot summer nights lit up by fireflies, for dogwood trees and Spanish moss. I was so angry at the way many Southerners voted, but I was more infuriated that everyone else used it as yet another excuse to dismiss the region.

I thought of the essay I wrote about my grandmother. I’d never begin to understand her, myself, my neighbors, or the land we’re from if I didn’t breathe it, interrogate it, work to better it. The South, despite its many faults, is a “place that I love more than I loathe,” as author Jesmyn Ward wrote in her 2018 essay.

It was time to go home.

* * *

On a frigid afternoon almost exactly a year later, my dog and I scrambled to the top of Silar Bald in western North Carolina, surrounded by waves of Blue Ridge Mountains. The Rockies are dramatic, but the Appalachians have such an ethereal quality — quiet and often misleading. They hold secrets and dangers that few know or understand, are majestic in a way that isn’t obvious unless you’re standing above them. Their colors and shapes shift with the shadows of the clouds, telling stories of millennia past.

Since returning home, I had been freelancing for national and regional publications about climate change, environmental justice, and energy in the region. I wrote stories about how people interact with their environment, why they decide to protect it or harm it, how they will fare with the myriad ways it’s changing. I founded Southerly, a weekly newsletter curating overlooked news and longform journalism about ecology, justice, and culture in the region. The goal was to steadily grow it into a magazine that filled a gaping hole in coverage of the American South: the complicated relationship people here have with the environment.

The South stands to lose more environmentally and economically from human-caused climate change than many other places in the U.S., and we’re already experiencing the devastating consequences of a fossil fuel economy. According to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, which was released in late 2018, temperatures in the South from 2010 to 2017 have been warmer than any previous decade. Farmers in Florida and Georgia are seeing shorter seasons for crops like oranges and peaches. The outlook is grim for those who make their living through agriculture: 570 million labor hours will be lost each year by 2090 due to heat and precipitation patterns, causing farmworkers and laborers — many of whom are immigrants — to lose jobs and money.

The number of extreme rainfall events is also increasing — something that has hit close to home in every Southern state in recent years, from West Virginia to coastal and inland North Carolina, from the Florida Keys to urban Nashville. This wetter, hotter weather is causing new public health risks: it provides ideal conditions for vector-borne diseases like Zika, West Nile, and other poverty-related tropical diseases. Sea level rise is flooding roads and other infrastructure in Miami and New Orleans; more frequent hurricanes are decimating whole communities, like Mexico Beach, Florida, and flooding coal ash ponds, landfills, and hog waste lagoons that dot rural Southern landscapes.

Still, up on the mountaintop, the facts felt abstract. I was confronting them directly every day through my work, and yet I still felt removed from the consequences. Southern states have some of the highest poverty rates and unemployment rates in the nation because of the downturn of the coal, manufacturing, and agriculture industries. Whole regions in the Mississippi Delta and Appalachia still lack access to basic resources like clean drinking water, unpolluted air, and proper sewage systems. Many people, especially in rural places, are just trying to survive each day, put food on the table, find a temporary job and affordable medical care. Expecting them to accept and claim responsibility for climate change, when no one has outlined solutions for these foundational problems, seemed unfair.

I spent the rest of that winter traveling around the South, reporting and attending conferences. Winter feels more honest here, all of our decisions laid bare. The lush greenery of summer can shroud our secrets—the mined land, the God-fearing religious billboards, the Confederate flags. Poverty is more visible, and clear-cut forests are easier to spot. Cold, crisp streams aren’t buried from view. Black coal seams stand out from the sides of icy cliffs.

“I was taught by my grandmother the importance of knowing local flora and fauna and geology and myths,” wrote Caleb Johnson, who analyzed author Gabriel García Márquez’s road trip through Alabama for The Paris Review, “as if this information might in some way protect me or at least bring me closer to the knowledge that in the eternal history of the world, I was the equivalent of a speck on a fly’s back.”

I focused on the details of these immense changes, followed their threads one at a time. A Kentucky county fighting to fix its failing water system, contaminated by the coal industry and crumbling from aging pipes, symbolized the region’s larger infrastructure failures. A train filled with New York City’s raw sewage stuck in an Alabama town made it clearer that poor Southern towns are treated as a dumping ground for the rest of the country. Agricultural runoff from the Midwest was depleting oxygen and killing off fish in the Gulf of Mexico, raising economic concerns in coastal communities. A hiking club in Eastern Kentucky helped people realize how few accessible public lands there are in Appalachia. The reasons rural Tennessee mayors started pushing solar energy offered glimpses into a new energy economy.

As I moved closer, the abstracts began to fade. Instead, I found rivers and forests with names, hollers with generations of history embedded in the soil. I found families. I found people.

* * *

On a balmy May morning last year, I unzipped my tent on Holly Beach, Louisiana, where I was camping for a night while on a reporting trip for Southerly, traveling from Montgomery, Alabama to Houston, Texas. Gentle waves delivered trash to the shore — a rubber clog sole covered in seaweed and clams, an ancient bottle of detergent, a Bud Light sticker. The air was already dense with heat, the sand fleas hopping and biting. Sandpipers scurried around, looking for breakfast.

In just a few months, Southerly had grown substantially, and we were launching as an independent publication and publishing a series on how communities were addressing the rise of poverty-related tropical diseases in the Black Belt, co-published by longtime newspaper Montgomery Advertiser and a newer regional outlet, Scalawag.

The project, and Southerly’s broader approach to reporting, focuses on potential ways to address these issues, rather than just describing insurmountable problems. Historically, the media has focused on the latter for the shock effect — especially when it comes to climate change or environmental issues — rather than analyzing ways local and state governments are failing, or how local residents and activists’ ideas could potentially work. It’s one of many reasons Southern communities of diverse demographics have been convinced there’s no way to improve public health or stop ecological degradation.

In his book, After Nature: A Politics for the Anthropocene, Jedediah Purdy describes this: “If you live in a wooded suburb of Boston and treasure the preserved lands next door, if you live in the dense neighborhoods of Boulder, Colorado and like to go to Rocky Mountain National Park for your summer hikes, your relationship to the land is secure, a privilege enshrined in law. But if you love the hills of southern West Virginia or eastern Kentucky, if they form your idea of beauty and rest, your native or chosen image of home, then your love has prepared your heart for breaking. ”

There are some places that can’t be saved, some people and species that won’t be. To love this region and its landscapes is to become accustomed to heartbreak. The unprotected land will continue to be developed by fossil fuel companies, despite the opportunity for renewable energy projects or agriculture. Coal companies and the lawmakers they donate to have abandoned toxic mine lands and miners dying of preventable diseases. The health of forests and water is deteriorating. The most vulnerable people among us are already suffering from flooding, storms, and pollution.

Seven feet above sea level on Holly Beach, surrounded by footprints of the oil and gas industry, I found the fatalism creeping in on me, too. Nestled near Lake Charles in Cameron Parish in the southwestern corner of Louisiana, Holly Beach is sandwiched between the Gulf Coast and miles of wetlands. For years, it was a Cajun Riviera destination; people came from all over the region to camp on the beach. It had an ice cream shop, dive bars, grocery stores, and hundreds of camps and cabins home to generations of Louisiana residents.

In 2005, Hurricane Rita brought 16 feet of storm surge and wiped Holly Beach off the map. Only a few rows of houses remain, most of them mobile homes on stilts. Building codes now require houses to be 20 feet above sea level and there are strict septic tank rules, so when residents started to rebuild, prices were much higher. Most decided not to. There are no more grocery stores or bars, hardly any street lights. That evening, cloudless and breezy, not a soul was outside.

Still, Holly Beach is authentically American, and being there made me feel patriotic and ashamed, fearful and optimistic, heartbroken and in love. Although the water was encroaching, the tent getting sandy, I didn’t want to budge, didn’t want to return to the week or to the stressful, contradictory realities of this world we’ve created. It made more sense why the people who live here are okay being invisible, why they might not want to talk about climate change and coastal erosion — and why, because of this lifestyle, they don’t have to until they must.

As I left to finish the reporting trip, I paused at all four unnecessary stop signs along Holly Beach’s short, deserted road, even though no other cars were in sight. I’m not sure if I’ll ever step foot on that beach again, or if it will exist by the end of my lifetime. I memorized every shade of blue, took a deep breath of the salty air, just in case. Growing used to heartbreak doesn’t mean accepting it.

* * *

During the cold, grey days of February this year, I moved to Knott County, Kentucky, just an hour’s drive from where my grandmother was born. The child in me hopes I will feel closer to her here. That maybe, if I scramble up the same mountains, learn to cook regional dishes, pick up some of the same dialect, wade through the same streams, part of the void she left will be filled.

Doing this means getting close to the details. It’s intimidating, dissecting a place you have emotional ties to, a place you’re fearful of and resentful of, a place you’re hopeful for. When you constantly search for truths, you run into a bottomless pit of uncomfortable and painful ones.

The South, like most places these days, feels increasingly divided, largely thanks to a concerted effort by industry and politicians to make it so. But as more injustices come to light, it becomes clearer how intertwined these challenges — and their solutions — are.

For instance, communities in West Virginia, Virginia, and North Carolina living along the route of two major natural gas projects, the Mountain Valley Pipeline and Atlantic Coast Pipeline, have for several years been fighting Dominion and Duke Energy over property rights, water quality certifications, and tree-cutting. Through months of reporting, I’ve found that it wasn’t until a regional coalition formed about a year ago that many people realized they were not isolated in their legal challenges against the utilities and began working together to monitor, regulate, and stop the projects.

The South, once divided from the rest of the country because of its support of slavery and kept at arm’s length ever since, is slowly starting to feel more cohesive. Local and regional media are collaborating more frequently with national outlets. Progressive candidates from historically underrepresented populations are beating incumbents who have kept the status quo. Community organizers are revamping the labor rights movement for teachers, miners, and other workers, and using new strategies to get people to care about the environment.

“We’re learning how to do together what we can’t accomplish apart,” Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson, the first black woman to serve as executive director of the nearly 87-year-old Highlander Research and Education Center in New Market, Tennessee, told me one frigid December morning as she looked out over the Smoky Mountains. “We don’t need a false sense of unity. We do need to see where there are points of alignment so we can struggle and debate and work and sum up lessons and figure out the next point of alignment to work toward.”

I often wonder how those points of alignment will shift and change as the climate does. The stakes are constantly rising, and the urgency to address new challenges grows while many of the people in power continue to dig in their heels.

It’s an eerie feeling, growing more attached to the South in a time like this. I know that entangling my career with my grandmother’s memory will lead to its own heartbreak. No matter how close she feels or how much I uncover, I’ll never know her. But to share the same space, to know the soil, the morning mountain fog, the rhododendron and pawpaw trees — it feels like a start. If I can better understand her roots, my hope is that I can find more common ground with the people this work is for and about, and more beauty and justice in the world around us.