They came together with shared concerns for the environment, the health and safety of residents, and for transparency in the business practices of Intel and its suppliers in western Licking County.

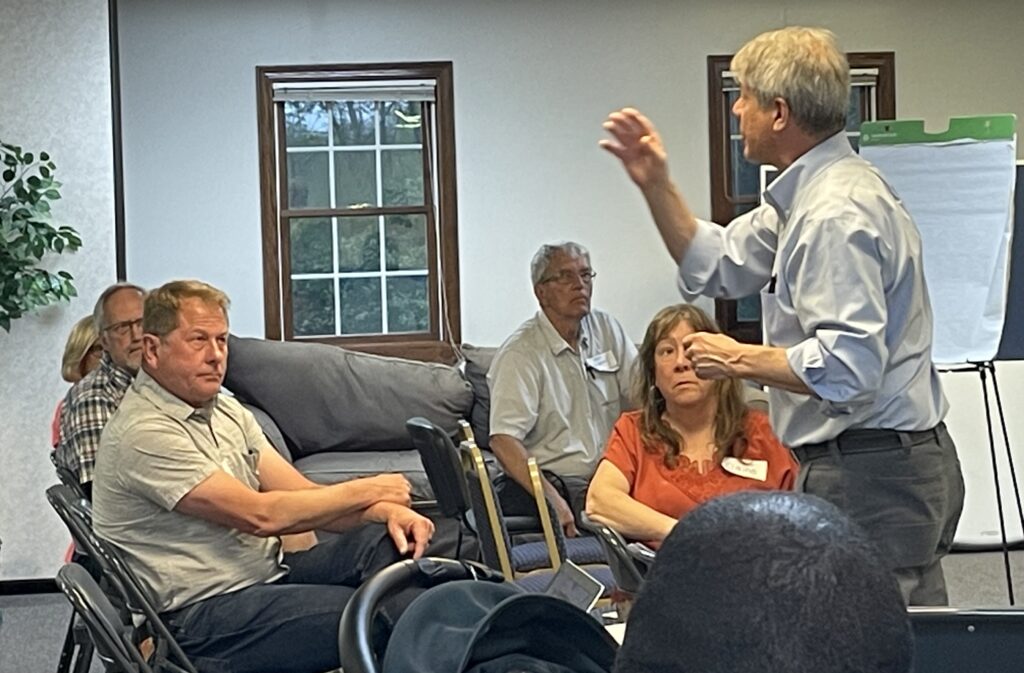

More than 50 people attended a meeting near Alexandria on the evening of Monday, April 29, to hear about a coalition called CHIPS Communities United and learn how people living near existing and planned computer-chip factories being subsidized with federal and state funds are dealing with the manufacturers and concerns about how they operate.

“The track record of the industry isn’t great,” said Rand Wilson, a Boston-based representative of CHIPS Communities United, in discussing violations of environmental regulations and the challenges communities have faced in obtaining details from chip manufacturers about the chemicals they use to make chips.

“Intel’s line is, ‘Don’t worry, be happy,’” Wilson said. “It behooves you to trust but also verify. … A principal concern is what gets released into the air and released into the water, and the concern about using so many billions of gallons of water,” he added.

The meeting at the Church of Christ at Alexandria was organized by Clean Air and Water for Alexandria, St. Albans Township and Granville.

Intel is building a $28 billion computer-chip manufacturing facility on 1,000 acres of former farmland just south of Johnstown in the New Albany International Business Park. The company based in Santa Clara, California, initially said it would begin production in Ohio in 2025 but now estimates it will begin in 2027.

CHIPS Communities United is a coalition of unions and environmental groups that Wilson said are focused on protecting workers’ rights to join unions, if they choose to do so, and the health and safety of those workers and area residents from toxic chemicals. Many of these chemicals are not disclosed by chip manufacturers because Intel deems them confidential and the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency allows Intel to shield those details as “trade secrets.”

Carol and Ken Apacki of Granville, who helped organize the meeting, said their research shows that air emissions from computer-chip factories elsewhere in the U.S. have made some nearby residents ill. And Carol Apacki said that when Intel would not say what was in the emissions, residents near a factory in New Mexico “passed the hat” to collect donations to buy monitoring equipment to learn for themselves what was in the emissions.

Hours before the community meeting, Emily Smith, Ohio Community Relations Director for Intel, sent out the latest in a series of email newsletters describing some of Intel’s environmental initiatives.

“We know transparency is important, and throughout Earth month, we’ve issued multiple newsletters with details about Intel’s environmental stewardship programs and sustainability efforts,” she wrote.

“In the first issue of our Earth Month newsletter series, we cover how we are protecting air quality and reducing our air and greenhouse gas emissions,” Smith wrote. “In our second issue, we shared Intel’s global water strategy to reduce, reuse and restore water, and photos of the superload and the route from Adams to Licking County. In the third issue, we shared Intel’s approach to energy conservation and renewable electricity. We also revealed the name of the first Buckeye tree planted on the Intel Ohio One Campus!”

When discussing priorities for community action going forward, Wilson and several in the audience suggested pressing county, state and federal elected officials – especially about 20 members of Congress who represent communities where computer-chip factories are receiving federal CHIPS and Science Act funds – to require manufacturers to meet with and work with local residents about their concerns.

He said the members of Congress should push Intel to develop a “community benefits agreement” that would hold Intel accountable to the community. Several people at the meeting also suggested that elected officials should require some CHIPS Act funds to be used to monitor Intel’s compliance with environmental regulations.

Granville Mayor Melissa Hartfield said that, to date, all levels of government above the local level have failed to ensure the safety of Licking County residents.

“We’ve been failed by all of the safety nets there to catch our fall,” she said, noting the billions of dollars in taxpayer funds subsidizing the Intel project. “We’re paying to poison ourselves, is in essence what we’re doing. We’ve been patronized. The more we show up, and the more we raise Cain, the more they want us to go away.”

The majority of people attending the meeting were from the Alexandria and Granville areas, based on a show of hands, and a few were from Columbus.

Bill Lyons, of the Columbus Community Bill of Rights organization, raised concerns about water consumption and the treatment of wastewater from the Intel campus. The City of Columbus has committed to supplying water to New Albany for the first phase of Intel’s operation.

“New Albany has shared with Columbus details of its direct discussions with Intel involving numerous infrastructure and economic development details, including water supply,” the Columbus Public Utilities Department said in a statement to The Reporting Project in March.

“Intel projects its maximum Phase 1 water needs, combined with expected nearby businesses, at six million gallons per day (MGD),” the utilities department said in the statement. Public relations specialist George Zonders said the statement was approved by officials at Intel and in the cities of Columbus and New Albany.

The Columbus statement also noted that, “Along with the water service agreement, New Albany is also one of more than two dozen suburban communities that has a sanitary sewer agreement with Columbus. Intel will be located within New Albany, and in accordance with our sanitary sewer agreement, Intel will be a part of our pretreatment program with the need for pretreatment evaluated through that program.”

Wilson said at Monday’s community meeting that Intel officials “say they are going to clean the water and put it back into the environment,” and added that without knowing which chemicals the company will use, it is difficult to know how best to monitor the treated wastewater to know how clean it is.

In Smith’s latest Intel newsletter, she wrote that “water for the Intel Ohio One site will come from the City of New Albany, which purchases water from the City of Columbus, which comes from Hoover Reservoir in the Upper Scioto Watershed along Big Walnut Creek.”

“After the water is used in the manufacturing process,” the newsletter says, “it will be treated and reused at the campus in multiple ways, before being treated again to applicable water quality standards (Ohio EPA and City of Columbus) and discharged into the sanitary sewer system where it is further treated at the City of Columbus’ wastewater treatment plant. There will be no direct wastewater discharges from Intel’s manufacturing operations to any water bodies. In accordance with our stormwater discharge permit, only stormwater is allowed to drain from the site into streams or surface waters.”

Intel says that stormwater is diverted into retention basins released gradually to prevent flooding and erosion. “These basins will be enhanced with wetland vegetation, which filter stormwater, and provide a natural habitat for plants and animals,” the Intel newsletter says. “These types of engineered wetland detention systems are the most effective stormwater quality management practices.”

Several community meeting attendees suggested that now is the time to take baseline measurements of water and air quality so that it’s possible to detect any changes after Intel begins making chips.

Kristy Hawthorne, program administrator for the Licking County Soil and Water Conservation District, said during the meeting that her organization is using grants to measure water quality and flow in Moots Run and Raccoon Creek, both of which have headwaters in western Licking County. Denison University Environmental Studies faculty and students also have been doing water-quality analyses of streams in western Licking County for the past two years, which provides a baseline from before Intel construction began.

Hawthorne said current grants allow for testing water for a handful of contaminants related to farming and asphalt manufacturing, and she is seeking additional funding that would allow testing for “forever chemicals” and others that could be used in computer-chip manufacturing.

When someone asked whether anyone from Intel was in the room for Monday’s meeting, no one responded. Ken Apacki said an Intel representative was among those to whom he sent email invitations.

Margaret Toland, a resident of St. Albans Township, said she would like to have seen someone from Intel attend so that “we could have a dialogue rather than a monologue” to address community concerns – especially about potential pollution and its health effects.

“I can live without computer chips, but I can’t live without my health,” she said.

Alan Miller writes for TheReportingProject.org, the nonprofit news organization of Denison University’s Journalism program, which is funded by the Mellon Foundation and donations from readers.