Place and Change in Eastern Ohio

Jefferson County, shaped like a keystone standing on its end, borders the Ohio River in the east across from the narrow peninsula of West Virginia separating Ohio from Pennsylvania. Known to locals as the Tri-State Area, the region is contained in the Allegheny Mountain foothills drained by the river. Yellow signs warning “FALLING ROCK” greet drivers on roads walled in by stone. The culture leans toward the east: educational television comes from Pittsburgh, the best newspaper from Wheeling. During the mid-20th Century, West Virginians commuted or moved to Ohio for jobs; people in Jefferson County reversed this trend and drove across the bridges to Wheeling or Weirton to work in the mills which, while dingy and polluting, paid well.

The most notable poet from the area, James Wright, fashioned his artistic voice from the speech of the people of the Ohio Valley and created a landscape both industrial and pastoral, portraying the mill jobs as dead ends but presenting the workers sensitively, as fugitives in their own land. What Wright captures so eloquently about that region, however, is the contrast between the dreary factories surrounded by brothels, mines with their slag heaps, the itinerant laborers, and the fields and woodlands around them whose “citizens” are farm animals and wildlife. Beyond the industrial hell and the banal suburbs rise the beautiful forested hills—at least those not yet logged or mined. It is an ironic pastoral because it is overlooked, preserved more often by neglect than by love.

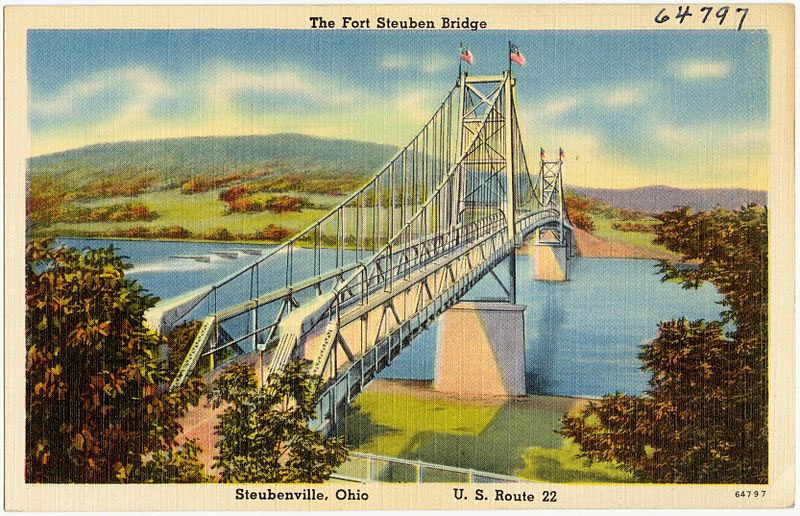

The Jefferson County seat, Steubenville—named for the Revolutionary War general Friedrich von Steuben—enjoys the reputation of being a sort of smaller Youngstown run by organized crime, and is rife with bars, prostitution, and illegal gambling. Growing up there as a child, however, I was unaware of the existence of organized crime and formed the impression that it was the churches that dominated. The city lies along the Ohio River and climbs the hills that rise from the valley. Until the advent of cheap imported steel, the town was kept alive by mills that sent their smokestacks into the air along the river (earning for the town the distinction of being the dirtiest municipality in the country in the 1960s). It seems run-down, but I think the Victorian houses and crumbling pavements give it a certain Old-World charm, as did the horse trough alongside Market Street that stood until the road was widened into a four-lane highway.

Beyond the industrial hell and the banal suburbs rise the beautiful forested hills—at least those not yet logged or mined.

I first learned to love the natural world when my father took my older sister and me for a walk in a cemetery near his boyhood home on Market Street, the main road into Steubenville, and taught us the names of the flowers and plants. An ivy-covered stone cottage, now an historic dwelling, served as the caretaker’s residence. Large trees shaded the entrance and several acres at the front. When the landscapers created the park, they left much of the area as it was, taking advantage of natural formations like stone outcroppings, slopes, and creeks.

Once inside the garden’s iron gates, the visitor was unaware of the busy city. The lawn dipped to a creek along which grew flowering shrubs: rhododendron, forsythia, holly, lilac. Where the canopy was thinner, wild plants thrived. As we walked farther, my father pointed out the black locust, oak, maple, poplar, tulip tree, sycamore, and willow. I began to see beyond the shady mass to the shapes of leaves, textures of bark, variations of color. He reached down and pointed out beneath mayapple leaves tiny bluebells nearly out of sight. In the newer part of the cemetery the trees were fewer and smaller, the landscaping more recent, and the birdsong less varied. Many indigenous plants survive in our time in part because of old cemeteries, where the ground is less disturbed.

My father had good reason to know well that cemetery in Steubenville. He had grown up in a large, multi-generational house, the veranda of which looked over the park. They had two outbuildings–a barn, which served by that time as a garage, and a livestock shed–on about half an acre of land. My great-grandmother, grandmother, grandfather, great-aunt, and great-uncle had grown up on farms and spent most of their lives there. In later years, all were buried in that cemetery, but not before the city had appropriated the house, lawn, out-buildings, orchard, and garden, as well as a sizeable corner of the cemetery park, to widen the road that passed in front of the house and make a cloverleaf interchange.

For forty years my parents lived in a farmhouse among hills to the west of town. Although I lived there only eight, I still refer to it as “home” because I believe that, for all our wanderings, “home” is the place that forges our character. The owner had sold the hundred or so acres around the house to a contractor, one of those people now called “developers” who buy up land from retiring farmers and subdivide it. He did not begin to build immediately, however, and during the first few summers I lived there, I rode ponies boarded on his land and wandered in his woods. The best season was the autumn, when the leaves turned red and gold, and puff balls on fallen tree trunks spouted golden dust when I touched them.

Some years later I returned from school to find a section of the woods ripped up by bulldozers. In a single afternoon about fifteen acres of large trees had been toppled and lay on their sides, enormous roots exposed and still clinging to ripped-up clods of earth. I walked among the trunks like battlefield dead, bitter about the maliciousness of destruction. Still, the land was not immediately developed; the owner, a cattle breeder, fenced it off and re-seeded it to increase the grazing land for his Herefords. He even left about twenty of the largest trees standing. It looked bucolic for several decades before he finally sold it off in lots where people built what were then called “monster houses,” which are now common. Suburbanization increased even as the population of the area declined.

Contractors posed a smaller threat to countryside and forests than strip mining, which desecrated more acreage in Jefferson County than any other in the state. Anyone growing up in eastern Ohio is familiar with it. Strip-mining “shovels” are machines as big as small houses with “buckets” large enough for people to stand up in. They tear up whole landscapes in order to lay bare the coal that lies near the surface and in doing so release toxic runoff.

By the 1970s bituminous or “high sulfur” coal, the type mined almost everywhere in Ohio, was already being vilified as the cause of acid rain that was killing the forests of New England. I assumed that strip mining was on its way out.

Of course, I was wrong. Years later as I was driving west on Route 22 towards home I looked up expectantly to see a vista I had loved for years: four layers of wooded hills rising blue on paler blue in the distance. The view had changed, however. The bucket of a strip-mining shovel was just barely visible beyond the last ridge. The next time I traveled that road, the hills had been stripped of trees and leveled.

According to state laws enacted in 1972, strip-mined land must now be “reclaimed.” The strip pits are bulldozed over and landscaped, and sometimes even sculpted back into hills, although not the jagged steeps they once were. A local can tell which slopes are natural and which are reclaimed strip land. The reclaimed ones have rounded tops, some of them dotted with sheep or cattle. They are seeded and sometimes planted with trees, although it takes 50 to 100 years for the woods to become forests again.

Since I grew up during the movement to restore the strip-mined areas and saw the passage of the federal Clean Air and Clean Water Acts (1970 and 1972), I believed people were going to reverse the trend of exploiting the earth.

In 2012 I learned how wrong I was. Jefferson County sits over the Marcellus Shale, rich in natural gas and oil, and is once again being mined, this time by horizontal hydraulic fracturing, a process in which millions of gallons of water mixed with hundreds of thousands of gallons of toxic chemicals are pumped into the ground in order to break apart shale deposits and release natural gas, which is sent via pipeline to compressor stations. Accidents from fracking sites resulting in contaminated water, air, and soil in Maryland and Pennsylvania are well-documented. Once containing the largest amount of strip-mined acreage in the state, Jefferson County now, according to Ohio Department of Natural Resources, has the seventh-largest number of horizontal gas wells. Out-of-state companies do most of the drilling and reap most of the profits.

To the west of Jefferson County is Harrison County, which has also seen its share of deforestation, strip mining, and horizontal hydraulic fracturing. In 2016, as part of the National Day of Action on Fracking, I visited Bluebird Farm near Tappan Lake, where a man named Mick Luber bought sixty-five acres in the Back-to-the-Land days of the 1970s—largely second-growth forest and reclaimed strip-mined land—and began an organic egg and produce operation using hand tools, self-built greenhouses, natural fertilizer, and ecological pest control. He made a living selling organic produce to specialized markets in Wheeling and Pittsburgh.

In 2015, Luber’s farm was threatened by the Kinder-Morgan company’s plan to build a pipeline—named Utopia—through Bluebird Farm, which would be acquired by eminent domain. Mick and his neighbors launched a campaign to stop the project, including front-page stories in the Wheeling Intelligencer and Pittsburgh Press and editorials on WWVA and KQED. They won, but only partly. Backing down before negative publicity, Kinder-Morgan agreed to reroute its pipeline, but the new route directly adjoins Bluebird Farm.

Walking through the deep woods, one comes suddenly upon an enormous gorge carved through wooded hills to bury a twelve-inch steel pipe intended to transport ethylene and propane 270 miles to plastics manufacturing plants in Canada. Four miles from the farm, a compressor station stands on about six acres carved from the landscape.

Infrared photographs reveal what digital cameras cannot: these stations emit large amounts of methane, a greenhouse gas thirty times more potent than carbon dioxide. Rural areas over shale deposits across the country have become “sacrifice zones” where residents are considered, essentially, expendable.

The shady dell where I first discovered the delight of the earth has been paved over; the forested hills that rose like an eternal promise are a stripped moonscape; the woods I explored on foot and on horseback are now used as trash dumps by the people who built houses on the fields; reclaimed strip mines are turned into toxic waste pits and pipeline corridors.

Yet, I remember that second-growth woods spring from the cut old-growth; the indigenous grasses that we pull from our gardens remind us that their seeds live on in the soil, however much of it has been transformed.

Our bodies and our veins hold the remembrance of what the land was and may be again if we can cease to think of it in purely materialistic terms and accept it as a living thing.

The earth has made us what we are, sustains us, and will take us back again when we have seen our share of passing seasons.