Life after Incarceration

Dana Cashdollar had been in line since early in the morning. Short, with red hair and a mustache, Dana walked at the very back. He watched as the column of inmates shuffled along, down hallways, and through gates he’d never seen before, even after several years of being locked up at Ross Correctional Institution in Chillicothe, Ohio.

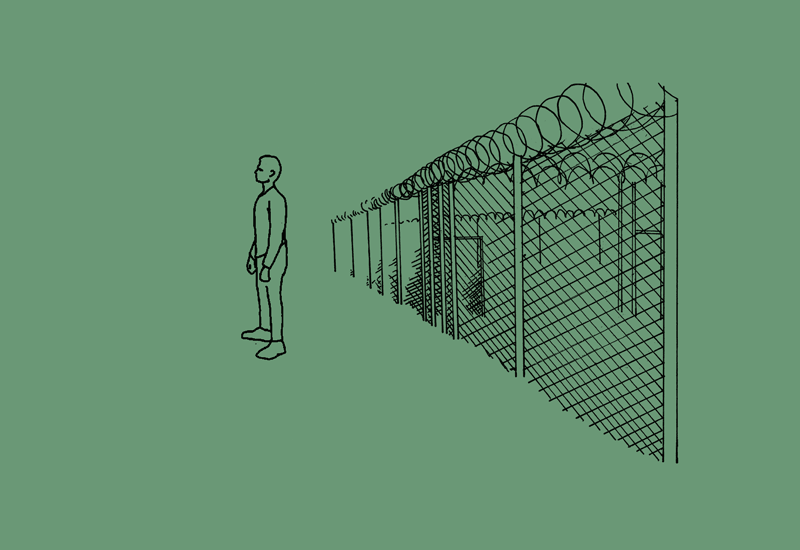

He was being led toward a room—a last checkpoint before a waiting area with a door that opened on a half-full parking lot, a crisp breeze, and an open sky.

As he passed, a guard called out, “You ever come back, Cashdollar, I’ll give you a kidney shot.” Dana gave him permission to do that and a whole lot worse.

His daughter, his brother, and his mom were waiting for him in the lobby, ready to drive him home to Licking County. “My family was so excited for me that I almost forgot to be excited myself,” Dana remembers.

In Ohio, thousands of men and women are released from prison every year. According to the recent Licking County Reentry Summit, over 24,000 will return to their communities in 2017. In Licking County, where Dana lives, around a quarter of those released will probably be reincarcerated again within three years.

On his first day free, Dana had to adjust quickly. His brother handed him a new phone with a touch-screen—quite different than the flip phone he’d had in 2007. He also had to get used to not having cuffs on his wrists while traveling on the highway.

And he had to reorganize his life, beginning with documentation. To re-enter society–getting a job, opening a bank account, even going to a doctor–Cashdollar would need a social security card, birth certificate, and state ID, none of which he had.

Dana Cashdollar had to start over.

Wendy Tarr, a criminal justice advocate and program director for Vincentian Ohio Action Network, believes that the justice system should better prepare inmates like Cashdollar for release, sending them through the gates with more than a few dollars in their pockets.

The first days out can be make-or-break for people just out of prison, and having immediate access to resources and to a positive social network can be a gamechanger.

“For people to be released from prison and not have an identification card, an adequate identification card, that becomes a problem,” Tarr says. “You would think that while they have the inmates physically there the government could coordinate to provide those things before they are released.”

While some Ohio prisons do supply inmates with paperwork that includes the forms necessary to get a valid state ID, this packet lacks social security cards or birth certificates. Even with the ID forms, returning citizens still have to make the trip to the DMV, which can be difficult for many in Licking County who have very limited access to transportation. Few own cars, and public transportation is virtually nonexistent. Ultimately, the lack of paperwork makes it more difficult to access support services that help people put their lives back together after a prison sentence.

Cashdollar was lucky to have a family who could drive him straight from prison to the Social Security Administration office and the Bureau of Motor Vehicles. He did obtain his ID, but he was denied, without any detailed explanation, the emergency financial assistance from the Social Security Administration that he thought would be provided to him as a disabled citizen, regardless of his past convictions.

It’s not that Cashdollar doesn’t want to work, it’s that there are many barriers, beyond the fact of his conviction, in the way.

The most significant is a shoulder injury–a torn and damaged rotator cuff–that happened at the construction job he had before he was arrested. This injury grew more severe in prison, but he didn’t receive any treatment for it while incarcerated. After release, he saw a doctor who provided him with written instructions not to push or pull more than five pounds. He winces violently each time he tries to reach his head with his right arm. The doctors don’t know if the injury will ever heal, though physical therapy is helping.

Two months out of prison, Cashdollar is still unemployed and spends his days doing what chores he can around the shelter where he lives, searching for jobs online, and volunteering with the Newark Think Tank on Poverty, a community organization that advocates for ex-prisoners like him.

At a meeting of the Ohio Criminal Sentencing Commission in 2014, Gary Mohr, Director of the Ohio Department of Corrections, claimed that 26% of prisoners were incarcerated for drug offenses, but that between 70 and 80% of those individuals had histories of addiction. For many former inmates with drug dependencies, staying with family members or friends after release means setting up camp in an environment where substances are present.

As Wendy Tarr points out, “If your friends and safety net system are people with substance abuse problems, it becomes part of the culture of your home and your environment. It’s really tricky when you put someone in a situation where they have to choose between being homeless or moving into a place where they know people care and will put them up, but where there might be circumstances that could get them into trouble again.”

Chris Wills, another returning citizen, had to make this same decision. His first plan was to stay with his mother until he found work and made enough money to move out.

Housing was an issue because his conviction violated the policies of the residence where his mother lived. He couldn’t stay there and, lacking the resources necessary to find a place of his own, tried living for a time with his father and stepmother. This arrangement was unsuccessful for a variety of reasons and, ultimately, led him to restarting his meth habit.

Though his situation was devolving toward homelessness and, potentially, reincarceration, there was a turning point. As Wills recalls, “I went to church one day and prayed. God told me to get out of there. I called a good friend of mine and told him ‘Stuff ain’t right,’ and he helped me get to St. Vincent.”

The St. Vincent de Paul Haven is the same men’s shelter that took in Cashdollar. Wills was there for three months before he got his own place. While today he is employed and living in a transitional housing community, getting to this point took time, which put him at risk of a relapse and another prison sentence.

Wendy Tarr points out that finding work is only one of the challenges faced by people with criminal convictions that show up when potential employers run background checks. Others include a lack of affordable housing and undermanaged mental health and addiction issues.

“We incarcerate people at such a high level for using substances and maybe committing crimes that are linked to their mental health, “ Tarr says. “We use a ton of state dollars for incarceration, but those dollars could be utilized to help local service organizations provide people with the resources they need to stay out of trouble.“

Tarr thinks rehabilitation programs on the inside are inadequate. “The prison system is fundamentally not a social services, social work, or behavioral health organization,” she says. And, she says, it shouldn’t have to be.

“The primary function of the correctional officers is just to make sure people have three meals and don’t kill each other,” says Tarr. “They’re not trained social workers or trained therapists. That’s not really who they employ in these prisons.”

Eric Lee is a facilitator for Licking County Judicial Release Group Adult County Services. He sees relapses on a weekly basis and understands the root causes in a personal way.

Lee was released from prison in 1999. It wasn’t until 2003, however, that he got clean. “My wife called the police on me. I wouldn’t put my hands up against the wall. They bent me all up, cuffed me, stuffed me in the car, put me in jail overnight, and that next day is when I went in front of the judge.”

The judge told Lee the time had come, that he had to choose between the drugs and his kids once and for all. Lee says that the judge “didn’t think I could make the right decision,” but he was finally ready to change his life.

In Lee’s opinion, just going back to a family member or friend, not trying to find work, not trying to pay rent, is a recipe for failure. In his experience, “people are just going to look at you based on what happened in the past and they’re going to say no over and over again.” Ultimately, being rejected for a job, or being kicked out of housing, fuels the depression, stress, and anxiety that can steer people back towards drugs, and, in turn, back to jail cells.

He reminds the men and women he works with, “You can’t expect people that you’re depending on to care for you when you’re not really caring for yourself and doing the same old stuff that got you locked up.”

Lee remembers the job offer that saved him–working for $7 an hour at a local hotel. He took the job and stayed on for eight years. It gave him purpose and stability, something that had been lacking in his life before.

Dana Cashdollar spent his first night on the outside, shuffling around his daughter’s kitchen. She had visited him often while he was in prison, so he wanted to do something, anything, to let her know he appreciated her.

“I cleaned the kitchen for about three or four hours. Did all of her dishes, dried ‘em, put ‘em away. Scrubbed down all kinds of stuff.”

He pauses from the telling.

“I wasn’t interested in hitting the bar or doing any kind of stupid crap that’s gonna get me in trouble.”

At 4:00 AM, just a few lights were on. He worked a dish in the sink, the rag flopped and sloshed, plates clanked on the counter. These were the only sounds in the house.

His eyes glazed over, he says. Little by little his body relaxed in the dim light, and now, it seemed, only his hands were awake.

He remembers not wanting to sleep that night.

“I napped for about two hours, got up the next day and cooked some bacon. Man, yeah, cooked some bacon.”

Kellon Patey is from Nashville, Tennessee, and is a junior English major at Denison University.